Making ambient music: the science behind the calm

Ask the average person what comes to mind when they think of electronic music, and chances are they’ll mention nightclubs, dance music, pounding drums and euphoric, high-energy sensory experiences. Styles like techno, house and drum & bass are purpose-built for dancefloors; their ebbs, flows, builds and drops are all part of a larger choreography of releasing energy and emotion en masse.

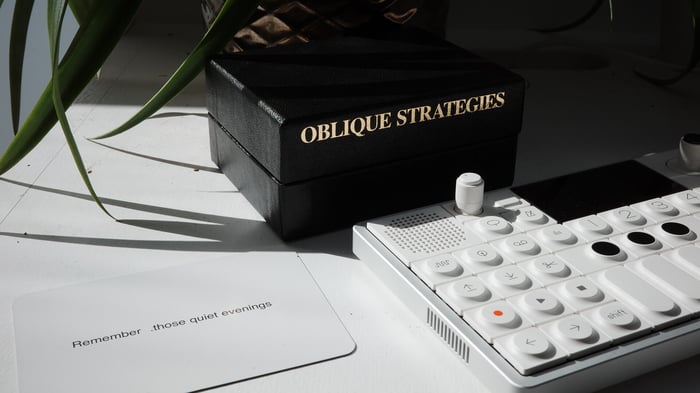

There is, however, a yin to this yang. On the other side of the coin lies the quiet, reflective but equally immersive world of ambient music. The term was originally coined by Brian Eno in the liner notes for 1978’s Ambient 1 / Music for Airports. He wrote: “An ambience is defined as an atmosphere or a surrounding influence; a tint… ambient music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.”

In the intervening years, ‘ambient’ has become a somewhat loaded term and is often used as a lazy prefix for styles of music that deviate quite significantly from this original definition. So for the purposes of this blog post, we’ll take ‘ambient’ to mean instrumental music that’s designed to produce a calming, relaxing effect.

With our increasingly hectic day-to-day lives and the growing focus on mental well-being, it isn’t surprising that such music is on the rise. But what’s actually happening to us when we listen to this music? And what techniques should we employ if we hope to make calming music ourselves?

Keep things slow

A 2017 study by Mindlab found that Marconi Union’s song Weightless reduced feelings of anxiety in test subjects by around 65%. The paper stated one of the main contributing factors was the tempo of the track; which is around 60bpm at the start of the track but over time decreases to around 50bpm. This is backed by a study in 2012 which found music around this tempo to be the most relaxing. The most likely reason is the link with the human heart rate: both are measured in beats per minute and 60bpm is a typical resting heart rate.

This is easy to incorporate into your songwriting - just adjust the tempo on your sequencer as required. However, the more adventurous could consider trying the ADDAC 307 Heart Sensing Eurorack module that generates tempo information and CV from your heartbeat via a sensor.

Keep things long

The same 2017 Mindlab study also found that it takes around five minutes for a process called ‘entrainment’ to take effect. Entrainment is the synchronisation of your respiratory system to an external rhythm, which in this case is music, though it could be another stimulus (for example the heart rate of your partner in a long embrace.)

It’s the lowering of your heart rate that gives you a calming feeling, and you can aid that process by keeping things at close to 60bpm for long periods.

Keep things sustained

A study from 1951 (further backed by the 2017 study) found that long sustained notes can make people feel ‘safe’. You want to avoid the abrupt feeling of short, intensely plucked notes if you want to keep things calming. Try to keep things at a similar dynamic range throughout: in many relaxing songs, a 5-second segment from almost anywhere along the timeline will be at a similar loudness and energy level to any other. You want to avoid any elements poking up at a level well above everything else.

That’s not to say you can’t have plucked sounds, of course - Music for Airports is all piano and vibraphone, after all, and using sounds with a more noticeable attack can help to define the tempo of a track better than something made up of only very slow building/falling sounds. Just bear in mind that soft, sustained sounds will maximise the relaxing effect.

Keep things repeating

Several studies point to the idea of repetition as a means of relaxation. Our minds are busy and often working in the background. Even when we’re passively listening to music, our brains like to find patterns. When you hear repeating melody lines or loops, your brain starts to realise what’s coming and so stops trying to guess what’s next. It can effectively ‘switch off’ a little, and that mental quiet has sedative results.

An obvious choice for doing this is using a looper, or having loops inside your DAW. The 5 Moons by Critter and Guitari is a great example: it’s small and easy to use, but most importantly it allows you to have each track independent in length to all the other tracks. Combining shorter loops and longer loops is a great way to create a composition that feels both new and familiar at the same time. Which leads nicely on to…

Keep things changing

This might seem to contradict the advice above, but having melodic lines that never repeat has also been found to have a similar effect, for the same reason as repetition. Our pattern-loving brains eventually realise that no pattern is going to form and so they stop trying to look for one.

So combining the random with the repeating can be a good technique. It’s also good to have solid foundations for the randomness - too much random can be a bad thing. In modular synths, controlled randomness might be achieved through stepped random voltages (sample and hold) that are then scaled and quantised to fit the key of your piece. Modules like the Make Noise Wogglebug or the Fancyyyyy Synthesis Rung Divisions are great ways of getting cool random voltages that you can quantise. Some modules offer both random generation and quantising, like the Michigan Synth Works Pachinko or ALM Pamela’s Pro Workout.

Another technique to introduce random variation is to play a looping melody with a sequencer that lets you control the probability that any given note will play, like the Squarp Hapax. These kinds of tools exist within a DAW environment too - Ableton added new probability features in Live 11, for example.

Keep things simple

I love ‘complex’ music as much as the next person, but triplet rhythms and clashing harmonies aren’t the best for keeping things very calm. If you want to keep the listener in a state of flow, then over-complexity runs the risk of pulling the listener out of the moment.

This doesn’t mean things need to be ‘simple’ or boring; working with Euclidean sequencers, for example, can yield interesting rhythms that still fit the brief. You want things to be rewarding when the listener pays attention, and the interplaying rhythms of Euclidean patterns can provide that. A great sequencer for this is the Torso T-1, and, in the modular domain, the previously mentioned Pamela’s Pro Workout makes Euclidean rhythms easy.

Likewise, to aid relaxation and promote feelings of security and comfort, keep the number of instruments to a minimum and keep the sonic palette consistent throughout, rather than bombarding the listener with maximalist sound design.

Parting thoughts

The above techniques are a pretty open-ended ‘how-to’ guide for ambient music, not hard and fast rules. Even within these loose guidelines, there is still a huge amount of creative freedom, and you’re of course free to employ as many or as few of the ideas presented here as you like when you’re composing.

Creativity arguably works best when you define enough restrictions to avoid getting lost in an overwhelming sea of choice, but not so many that you feel hemmed in and restricted. There is, as always, a balance to be found.

Further reading

Anthony Storr - Music and the Mind (HarperCollins)

Oliver Sacks - Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain (Vintage)

Daniel Levitin - This is Your Brain on Music (Penguin)